Informational Brief of Redistricting

Return to Redistricting Committee Main Page

Informational Brief – Link to PDF

August 2021

Redistricting Basics

Every ten years, based on data from the decennial census conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, Nebraska must draw new district maps to elect members of the Nebraska Legislature, the U.S. House of Representatives, the Nebraska Public Service Commission, the University of Nebraska Board of Regents, the State Board of Education and to appoint Judges to the Nebraska Supreme Court. This brief describes Nebraska’s redistricting process, compares the legal requirements for legislative and congressional redistricting, explains critical district-drawing terms, reviews landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions concerning redistricting and discusses operational delays caused by the COVID pandemic in 2020.

Redistricting Foundations

Nebraska elects its state senators and members of the U.S. House of Representatives from districts with equal populations giving every vote cast the same amount of political weight. After each federal decennial census, based on the updated population data, Nebraska is required to redistrict to maintain population equality between districts.[1]

Apart from this year, the U.S. Census Bureau has distributed new population data for redistricting by April 1 of each year ending in one (e.g., 2021). Per Rule 3, Section 6 of the Rules of the Nebraska Legislature, a Redistricting Committee must be established in January of each year ending in one, to introduce bills and resolutions relating to redistricting and hold hearings regarding the legislation. New redistricting maps are to be in place in time for the nomination of congressional and legislative candidates in the primary election held in April of the following year. This timeline is necessitated by the provision that candidates must meet a one-year residency requirement to hold office.[2]

LR 134, adopted during the 2021 legislative session, outlines the procedures to be followed for redistricting legislative and congressional seats and other statewide offices.

Comparison of Legislative and Congressional Redistricting

Nebraska uses a very similar process for legislative and congressional redistricting with the exception being the range of population deviation (the percentage by which a district’s population can vary from the point where all districts have the exact same population). The range of population deviation for congressional redistricting is +/- .5% (plus or minus one-half of one percent) and for the Legislature and other statewide redistricting plans, +/-5% (plus or minus five percent).

The following tables provide a comparison of the redistricting process for legislative and congressional districts.

Legislative Districts |

Congressional Districts |

| Who draws the districts? | |

| Nebraska Legislature | Nebraska Legislature |

| What is the Redistricting Committee? | |

| Rule 3, Section 6 of the Rules of the Nebraska Legislature requires that in years ending in one, a nine-member redistricting committee be assembled, with three members of the committee being from each congressional district, and no more than five members of the committee being from the same political party, to introduce redistricting bills and oversee hearings on the bills. | Same as for Legislative Districts |

| What is the timeframe to adopt a redistricting plan? | |

| No deadline is set in either the Nebraska Constitution or state statute for redistricting; however, Art. III, sec. 8 of the Nebraska Constitution requires that a candidate for the legislature must have resided in the district for one year before taking office. | Not Specified |

| How is population equality defined? | |

| ● District populations should be as nearly equal as may be, with a range of deviation of no more than 10% or a relative deviation above +/- 5%.

|

● District populations should be as nearly equal as practicable with a deviation range at or near zero; and

● No district may contain a population with a range of deviation of more than 1% or a relative deviation above +/- .5% of the ideal district population. |

| What are the redistricting standards the Legislature must follow? (As contained in LR 134 (2021)) |

|

| Mandatory Standards:

● Compactness; ● Contiguity; and ● A county with a population within the range of deviation must be kept whole and is entitled to a legislative seat.

Standards the Legislature must attempt to follow: ● District boundaries shall follow county lines when practicable; ● District boundaries shall not be established with the intent to favor a political party or any other group or person; ● No boundaries shall be drawn that consider the political affiliation of registered voters, demographic information other than population figures, or the results of previous elections, except as required by law or the U.S. Constitution; ● Shall not establish district boundaries that result in minority vote dilution; ● Preserve communities of interest; and ● Allow for the preservation of cores of prior districts. |

Mandatory Standards:

● N/A

Standards the Legislature must attempt to follow: ● Compactness; ● Preservation of municipal boundaries; ● District boundaries shall follow county lines when practicable; ● Preserve communities of interest; ● Allow for the preservation of cores of prior districts; and ● With all other criteria being equal, preference is to be given to the redistricting plan that provides the greatest degree of population equality. |

| How are legal challenges to redistricting plans handled? | |

| Challenges to redistricting plans passed and signed into law must be filed in the district court of Lancaster County, per Neb. Rev. Stat. §25-21,206. | Same as legislative districts |

Principles of Drawing Districts

Compactness

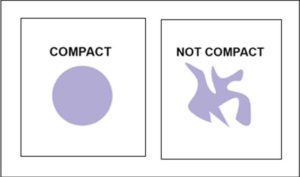

In redistricting, appearance matters, especially when it concerns the redistricting principle of compactness. Compactness is a redistricting principle that requires districts to be geographically compact, which means that the distances between the parts of the district or territory are minimized. There is no uniformly agreed-upon standard for identifying a compact district, but the U.S. Supreme Court has on occasion used an “eyeball test.”[4] Applying the “eyeball test” to the images below, it is easy to identify the geographically compact district from the one that is not as compact.

Examples of Compact and Not Compact Districts

Contiguity

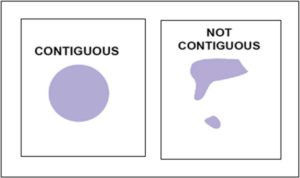

All legislative and congressional districts in Nebraska must be contiguous, which means that all districts must be a single, intact shape with all parts of the district connected. A contiguous district cannot be divided into two or more parts.

Examples of Contiguous and Not Contiguous Districts

Diluting Minority Voting Strength

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the federal Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, and Nebraska LR 134 (2021) prohibit a redistricting plan from denying or impeding a citizen’s right to vote based on race, color or status as a member of a language minority group. To identify minority vote dilution as it pertains to the VRA, the Supreme Court has adopted what is known as the “Gingles’ Test” which requires that to succeed in a legal challenge on a vote dilution claim, three preconditions must be met: 1) the minority group “is sufficiently numerous and compact to form a majority in a single-member district;” 2) the minority group is “politically cohesive, meaning its members tend to vote similarly;” and 3) the “majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it…usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”[5]

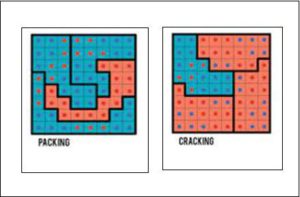

The most common practices used to dilute a minority group’s voting strength are known as “packing and cracking.” Packing and cracking are district drawing tools used to limit a particular group’s ability to elect a candidate of their choice, thereby giving them less political influence. The term “packing” means to squeeze voters of a particular group into a district well above the numbers required to win the district, reducing the group’s ability to impact the outcome of elections in districts outside of the packed district. Conversely, a group that is “cracked” has its membership divided among two or more districts for election purposes making it the minority group in more districts than their voting strength would otherwise provide, greatly diminishing their ability to win elections in those districts.

In the diagram labeled “Packing,” the red dots are packed into a single district where they have a majority. In the diagram marked “Cracking,” the blue dots are divided to such a degree they only have a majority in one district. In each diagram, both the red and blue dots could have influence in multiple districts if the districts were drawn to accommodate the number of dots represented by each color.

Examples of Packing and Cracking

Remedying Minority Vote Dilution

A remedy available to a court finding of minority vote dilution is creating a majority-minority district where a sufficient population of a minority group exists to allow that group to elect a candidate of its choice. A state with a history of minority vote dilution may voluntarily draw majority-minority districts to remedy its discriminatory history.[6] In some instances, however, courts have overturned a state’s effort to remedy its discriminatory history through the creation of majority-minority districts when the creation of those districts have been determined to be racial gerrymanders.[7]

U.S. Supreme Court Cases

The following U.S. Supreme Court cases are landmark opinions issued by the Court on congressional and state legislative redistricting. These opinions provide a sense of the competing interests states face when they redistrict. The list of cited cases is not exhaustive, and the rulings may have been altered by later decisions.

Population equality

- Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) – Provides that congressional districts within the same state must be “as nearly equal as practicable.”

- Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) – Held that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause requires state legislative districts to be substantially equal in population.

- Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) – Clarified that congressional districts must be mathematically equal in population unless the inequality is necessary to achieve a legitimate state interest.

- Evenwel v. Abbott, 136 S. Ct. 1120 (2016) – Held that states may use total population data to comply with the one-person, one-vote principle of the Equal Protection Clause.

Racial and language minorities

- Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) – Provides that a minority-majority district can be drawn under the VRA to remedy identified instances of minority vote dilution when three specific preconditions are met (the Gingles’ test discussed earlier in this brief).

- Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) – Held that a district’s creation that cannot be explained on grounds other than race, violates the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

- Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1996) – Clarified that a district is deemed to be racially gerrymandered if race was the “predominant” factor considered in drawing the district’s boundary lines.

- Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) – Held that a district drawn predominantly based on race cannot meet VRA requirements unless there is strong evidence that drawing the district was reasonably necessary to avoid denying or abridging equal voting rights.

2020 U.S. Census Data Delays

The Nebraska Constitution and LR 134 (2021) require the use of population data from the U.S. decennial census for drawing district boundaries when redistricting. By law, the Census Bureau is mandated to provide states with its population data for redistricting purposes by April 1 of each year ending in one.[8]

In February 2021, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Census Bureau announced that population data would not be delivered to the states by April 1. The Census Bureau indicated it would provide the local census data in the previously used legacy format to the states by mid-August 2021, and in the easier to use public format by September 30, 2021.[9] In response to the delay in receiving the data, the Legislature is tentatively scheduled to convene a special session in September 2021, for the purpose of redistricting.

[1] Art. III, sec. 5, Neb. Constitution

[2] Art. III, sec. 8, Neb. Constitution

[3] Day v. Nelson, 240 Neb. 997 (1992)

[4] Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 960 (1996)

[5] 52 U.S.C 10301, and Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986)

[6] Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146 (1993).

[7] Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) and Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, 135 S. Ct. 1257 (2015).

[9] U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau Statement on Release of Legacy Format Summary Redistricting Data File (March 15, 2021)